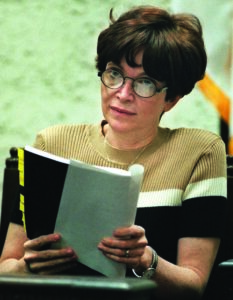

Susan Rosenblatt

A Tribute to Susan Rosenblatt

By Neil Genzlinger, a writer for the New York Times Obituaries desk. December 3, 2021

Susan Rosenblatt, who with her husband and law partner, Stanley Rosenblatt, took on Big Tobacco in a Florida case that seemed an absurd mismatch for their small firm, but that resulted in a record $144.8 billion jury award in favor of people sickened by cigarettes, died on Nov. 14 in Houston. She was 70. Her death, at MD Anderson Cancer Center, was confirmed by her son David Rosenblatt, who said the cause was acute myeloid leukemia.

Ms. Rosenblatt, who lived in Miami Beach, was the quieter side of the Rosenblatt firm; in the headline-making tobacco case and other prominent lawsuits, Stanley Rosenblatt did much of the in-court presenting and after-court news conferencing.

Susan Rosenblatt during the Broin Flight Attendant Class Action

But it was Ms. Rosenblatt’s legal scholarship — the research she did, the briefs she wrote — that provided the ammunition that made their successes possible. “I always would say I didn’t have a dream team, I had Susan,” Mr. Rosenblatt said in a phone interview.

That dream team (which also included a small support staff) was never more challenged than by the case the Rosenblatts filed in 1994 against R.J. Reynolds and other tobacco companies on behalf of seven smokers — one of whom, Dr. Howard A. Engle, was the pediatrician for most of the Rosenblatts’ nine children and became the lead plaintiff. The case was certified as a class action representing all Florida smokers, a group that encompassed hundreds of thousands of people.

The case, one of a number being pursued at the time against the industry by states and individuals, dragged on for years. In 1996, when the biggest of those cases, a national class-action suit, was thrown out by a federal appellate panel in New Orleans, Mr. Rosenblatt told The New York Times, “Now it’s up to Ma and Pa Kettle.”

He and his wife pressed on with the Engle case, arguing that the industry had knowingly addicted smokers and failed to warn them adequately about the dangers of their products.

Ms. Rosenblatt in 2004 with Frank Amodeo, one of the plaintiffs in the class-action suit the Rosenblatts filed in 1994 against R.J. Reynolds and other cigarette companies.

In 2000, a jury awarded several representative plaintiffs $12.7 million in compensatory damages, then followed that up with a stunning award of punitive damages to the whole class: almost $145 billion, the largest such award in history. The award didn’t stand; in 2003 a Florida appeals panel threw it out, finding, among other things, that the case should not have been declared a class action because each smoker’s case is unique. But the Rosenblatts’ efforts weren’t wasted: In 2006 the Florida Supreme Court ruled that individuals who wanted to pursue cases could invoke some of the original jury’s findings, including that smoking causes lung cancer, that nicotine in cigarettes is addictive and that the cigarette companies concealed information about smoking’s health effects. Individual suits, known as the Engle progeny cases, have been working through the Florida courts ever since, some successful and some not. Mr. Rosenblatt said the legacy of his and his wife’s work was the precedent. “The fraud, the conspiracy — there’s a record now of just how evil the tobacco industry had been all those years,” he said.

Susan Goldman was born on Jan. 5, 1951, in Brooklyn. Her parents, Sol and Shirley (Kaslow) Goldman, operated a real estate business together. When Susan was about 10, the family moved to Miami Beach. Academically, she was a prodigy, enrolling at the University of Miami at 13 and graduating in 1968 with a bachelor’s degree in economics. She graduated from the university’s law school in 1972. She received a master of law degree in 1978. She and Mr. Rosenblatt married in 1980. She maintained her own appellate practice until her growing family took precedence. “But after three children, I really was bored,” she told The Miami Herald in 1996. “I’m not the type to go out with girlfriends to lunch.” So she began working with her husband, even as their family continued to grow. “I was very fortunate to have easy pregnancies,” she told The Herald. “And the kind of work I do is reading cases, reading

depositions, preparing briefs, which I could do at home in bed. Although the Ma and Pa Kettle self-description was apt in some ways, the Rosenblatts were hardly neophytes when they took on the tobacco companies. They had won significant awards for plaintiffs in a number of cases. Most notably, they had already taken on the tobacco industry in another case, representing airline flight attendants who argued that their health had been damaged by secondhand smoke in the days when smoking was allowed on airplanes. That case, filed in 1991, ended in 1997 with a settlement in which the cigarette companies agreed to pay $300 million for the study of tobacco-related diseases.Ms. Rosenblatt said that she had been reluctant to take on Big Tobacco — “I thought it was chasing windmills,” she told The Times in 2000. But, her husband said, she came around and nudged him ahead, knowing he’d get a kick out of deposing the tobacco executives he had come to revile. “I think she was humoring me,” he said. “‘Take the depositions of these guys and have some fun, and it’s not going to go anywhere.’ And it took over our life.”

When the Engle case went ahead, the tobacco industry, as it had in other cases, tried to bury its opponents in motions and challenges, hoping to exhaust the lawyers and the plaintiffs. During the trial itself, which stretched for almost two years, the companies would sometimes bring in skilled lawyers just to examine a single witness or argue a single motion, Mr. Rosenblatt said, while he relied on his wife. “Sometimes, the only thing I’d use to cross-examine those witnesses was what Susan would have prepared for me,” he said. And while he was cross-examining, she would be working on what he needed the next day.

If Mr. Rosenblatt drew most of the attention, Ms. Rosenblatt was, as The Chicago Sun-Times described her in 2000, “the expert on the law balancing his expertise in front of the jury, the worrier compared with his slouching nonchalance, the detail person balancing his big-picture view.”

In addition to her husband and their son David, Ms. Rosenblatt is survived by two other sons, Joshua and Moshe; six daughters, Miriam Hoffman, Rachel Gdanski, Rebecca Assaraf, Jaclyn Richter, Rina Kleiner and Sharon Franco; a brother, Alan Goldman; a sister, Ruth Schwager; and 30 grandchildren.

Busy as they were, the Rosenblatts, who were Orthodox Jews, never worked on the Sabbath, yet Ms. Rosenblatt sometimes lamented that she spent so much time on cases at the expense of home life. Mr. Rosenblatt, though, said there was a philosophy behind their domestic madness. “Susan felt, and I agreed with her, that the most important thing parents can do is set an example,” he said.

Ms. Hoffman, the couple’s eldest daughter, said one bit of family lore merged Ms. Rosenblatt’s legal expertise and parenting skills. At one point, she said, her mother acquired a used mini-school bus — yellow, of course — to transport the brood here and there. A Miami Beach neighbor complained that parking a yellow school bus in a residential neighborhood was a violation of city code. Ms. Rosenblatt, Ms. Hoffman said, convinced an administrative judge that if the bus weren’t yellow, it would be in compliance. So she had the thing painted green.

“That was my mom,” Ms. Hoffman said by email. “She always had a special way of doing things. Unlike anyone else.”

Neil Genzlinger is a writer for the Obituaries desk. Previously he was a television, film and theater critic.